Founder and director of the Dulala association

Montreuil, France

Plurilingual Kamishibaï contest since 2015

Extract from an interview with Delphine Leroy on May 18th, 2021 in Montreuil within the framework of the Erasmus+ Kamilala project

The context

Many experiences led to the creation of the adventure that is Dulala, of which one professional experience was especially decisive. It was at the beginning of the 2000s, I had just arrived in France and I was teaching Italian in a public elementary school situated in a working-class neighborhood in Paris. Before beginning to teach, I would take the time to valorize the different languages of each student, to capture the meaning of this language learning: I made an effort to get to know my students, asking them what they knew about Italian as well as other languages.

This is where Dulala’s approach comes from: questioning the use of languages and revealing the interest of learning them with children. I realized the border that existed between home and school: the linguistic and cultural worlds were not permeable. The time taken to value them, in this school, gave rise to an overflow of joy […]. Children who were very shy – sometimes very noisy, but who never spoke up about school content – were, for the first time, very proud to say “But I know things, words”.

I was both very surprised and happy to see these results, which animated the class, and I shared them with the teachers. Some languages were “assumed” by the adults in the school, they said: “but yes, but you, Mamadou, speak other languages at home, it’s obvious.” But Mamadou had one language, only one, and it was French from the beginning. There was this important gap between the assigned world, assumed by the first name or the color of the skin, and the real language. I was shocked because, without a doubt, my personal story echoed theirs.

After a year, I said to myself, “This is what I want to do. I want to imagine, I want to create projects to value these incredible skills, even the smallest knowledge that allows children’s eyes to shine”.

Dulala’s project comes from this professional history – which reactivated elements of my early childhood – but also from my experience as a mother.

These different needs and observations led me to create Dulala, based on my studies in social and solidarity economy at the CNAM. The beginning was difficult but passion and the support of my family helped me to overcome the initial difficulties.

Bio

Dulala is also rooted in my early childhood. I was born in Veneto (Italy). Raised by my grandparents, we communicated only in Venetian. Both of them grew up with little schooling, making it difficult for them to speak Italian. As a little girl, I felt that Venetian was not valued: it was not to be spoken at school. This social divide, for me, was hurtful. There was a kind of ambivalence between the language spoken at home with my grandparents – the language of hugs, of reprimands, of childhood – and the view of society, of other educational actors who were concerned about my schooling.

As a child, I was ashamed that they spoke Venetian to me because it was “not appropriate” to speak Venetian to a child. I interiorized these representations, this denial, very early on. Later, I was ashamed of having been ashamed. This fed my

Once an adult, I moved to Russia for my studies, where I met my husband. We spoke Spanish because he didn’t speak a word of Italian and I didn’t speak a word of French. Over the years, I learned French and it became a language of everyday life, a language of professional use, of friendship. We practiced it at home.

Our family repertoire includes French, Italian and Venetian, all of which are spoken depending on where we are. Then there are the other languages learned through studying and by life experiences abroad: Spanish, Russian, English.

My daughter was born in 2005. The transmission of Italian came about almost naturally. Still, I looked around for groups of people, speakers with whom to share this language: at two and a half years old, I wanted her to speak and play in Italian with other children. A language needs a community to live and develop in, and I found nothing except classes, starting from 6 years old and organized mostly in a religious context (parish, mosque..)

The very first actions of Dulala were extracurricular bilingual workshops in Italian and Spanish, but I wanted this bilingualism to develop with all languages and not only languages that are already valued. To access minority languages, we had to enter the schools. We therefore proposed workshops in Wenzhou, Tamil, Soninke, Maghrebian Arabic… Then, thinking about it, we would have had to open as many workshops as there were minority languages, which was impossible. This observation, reinforced by the discovery of the project of opening up to languages at the Didenheim school, encouraged me to move on to another form of action, that of training teachers in a logic of empowerment. The first trainings started in 2011, two years after the birth of Dulala. One of the first systematic support projects (for all educational actors) targeted Rillieux-la-Pape, a city next to Lyon, for 3 years in the framework of a city contract. This community has included the issue of languages and plurilingualism in its educational policy project: it has taken up the project. A work of putting into words the representations of languages, language, family languages and the learning of French, the language of the school, was undertaken. This work has made it possible to reveal these themes, which were previously invisible. Some languages are perceived as welcome and others as harmful. Ideas of pollution between languages (especially the languages of immigrants) can persist. To defend them is to have an action in the public sphere, it is to carry a political project. These actors succeeded not only in formulating it as a major issue for their city, but also in setting up extraordinary projects that have lasted through changes in the municipal team, demonstrating that children and parents were more involved in the schools thanks to these actions and that the social link had improved.

The contest

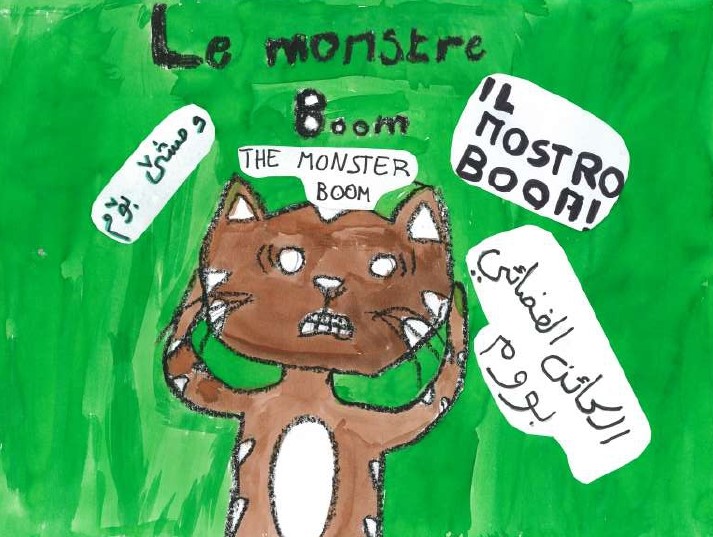

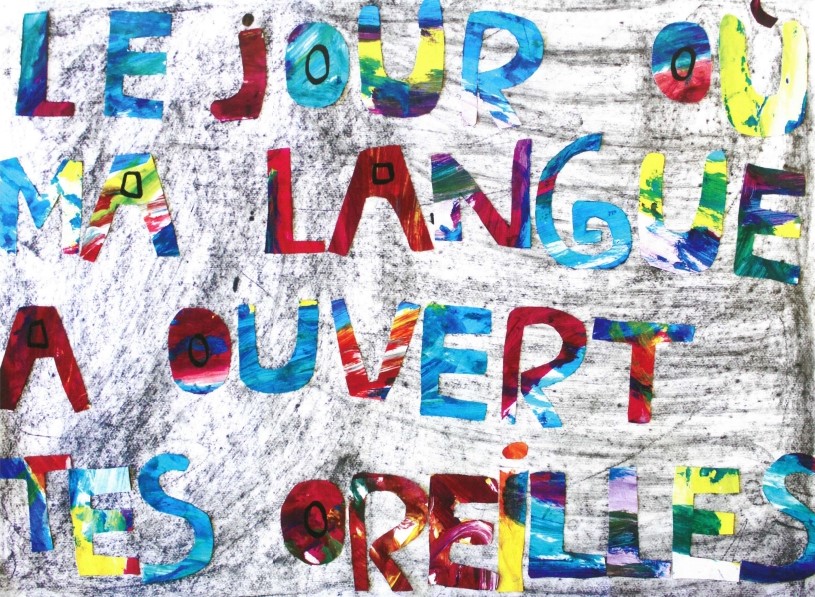

The Plurilingual Kamishibaï Contest was born five years after the beginning of Dulala, again thanks to my daughter. In 2012, she was 6 years old. At the end of the year party, the children of the class, divided into pairs, came to read a story that they had created and that the children of the neighboring school had illustrated: I discovered the kamishibaï, a writing and reading medium. I was impressed by the transgenerational, transdisciplinary and interclass dimensions. You could see the children’s eyes sparkle, the pride they had in themselves. I went back to Dulala and said to my colleagues, “You know what? There’s a Kami thing, kamichi, I don’t know what it’s called but something that looks awesome.” I didn’t know about kamishibaï at all, at the time.

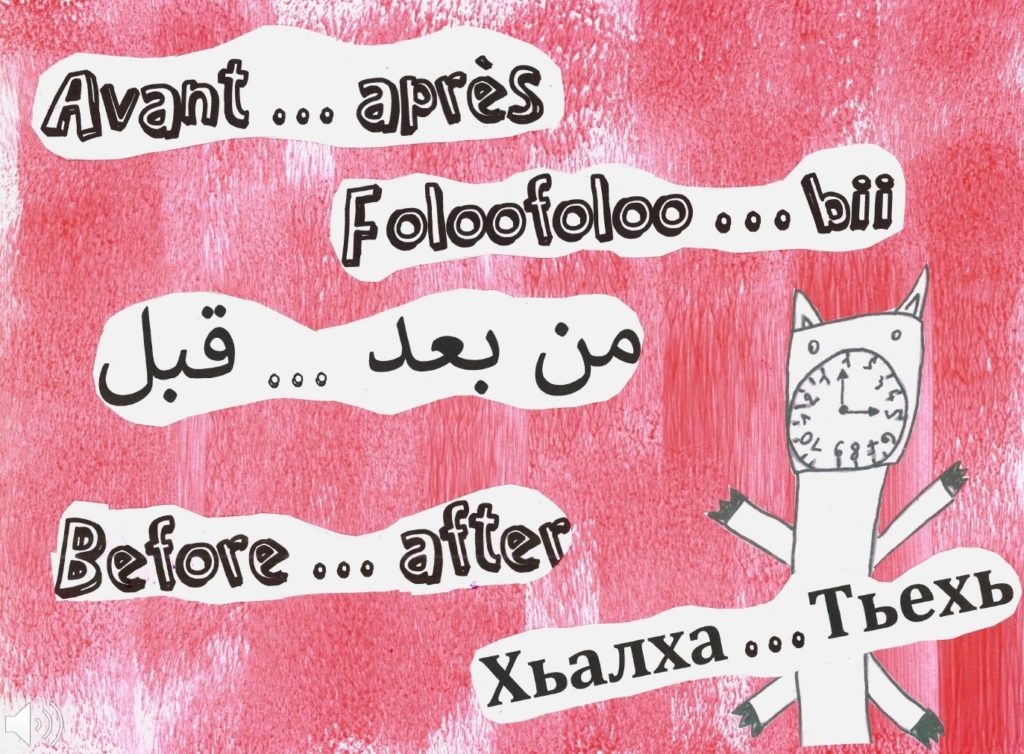

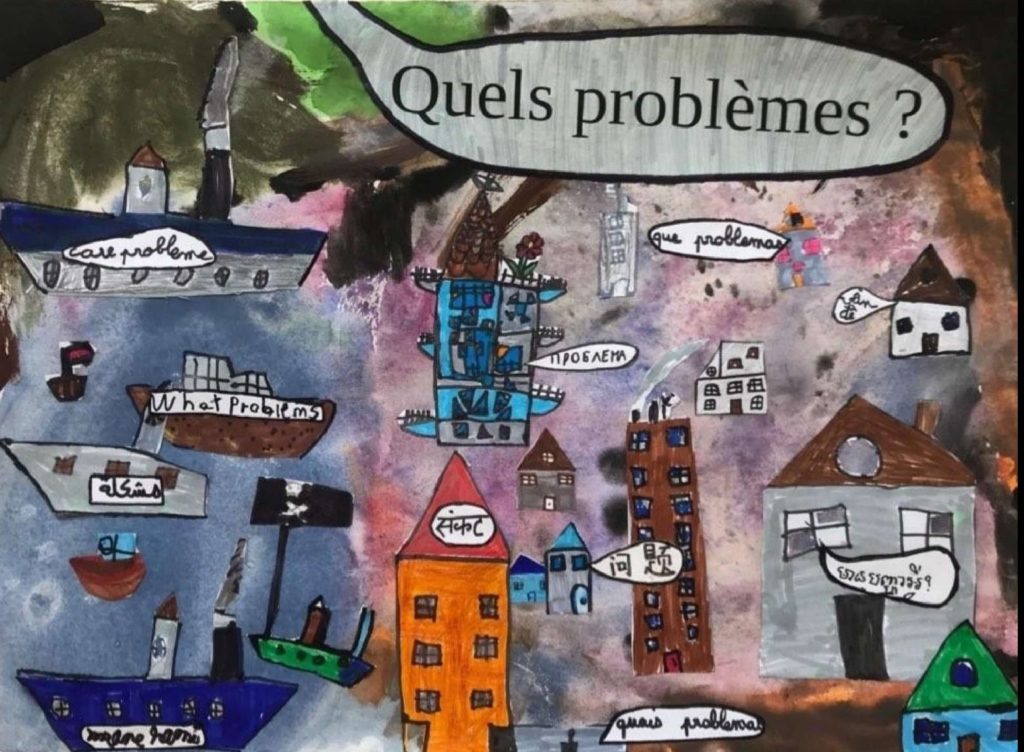

I imagined the pedagogical projects that this particular method of narration would permit, allowing the discovery of a lot of things. I told myself : “We produce resources all the time. What if we finally used this medium to get children to imagine, create and illustrate a story in a multilingual format? What I found interesting in this dynamic was to encourage the actors to produce their own tools with the languages of their group, with the resources available. But also to put the children in the position of author and illustrator, a powerful lever to engage them in learning, especially in reading and writing. The other considerable asset of this project is that it is very complete, it is part of a project-based pedagogy and all at once encourages working on visual arts, French, opening up to otherness and learning about otherness, cooperation, etc..

We launched the competition in 2014 and immediately received a huge number of entries (over 80). The announcement was made both at an educational conference and on social networks and the website. Many applications came from teachers with whom we had already worked but also from other educational actors from all over France, including rather rural regions, without much immigration but who found the projects interesting, because the challenges of openness to linguistic and cultural diversity are just as important.

This project appealed not only to “enthusiasts” of plurilingualism but also to a variety of educators: the word kamishibaï intrigued, and then its narrative construction aroused a form of attraction. The openness to languages generally came later: once they were involved in the production, the interest in working on plurilingualism became apparent. I remember in particular the testimony of a headmistress of a small school in Brittany who signed her letter “Nolwenn G., headmistress of a now multilingual school” because multilingualism had been revealed thanks to this project.

The success of the first edition led us to renew the competition by opening it up to the overseas territories, and then in 2017, to the different structures of the francophone world.

Determined to share this unprecedented experience of multilingual creation covering the issues of an education open to linguistic and cultural diversity, the team presented the kamishibaï competition at the EDILIC international association conference in July 2017. This is how project leaders in Portugal, Greece, Canada emerged. Since 2019, the network has continued to grow with various profiles and geographical locations (embassies, universities, communities, associations, training centers…).

At present, this beautiful dynamic, taken up by several project leaders, requires the transfer and sharing of didactic materials – the object of the European project – because Kamilala has become a larger, collective project. With the aim of institutionalizing it, the need to demonstrate its benefits by multiple actors in France, but also abroad, will contribute to validate it. The initial dream thus became reality: today, every year, thousands of children around the world learn, cooperate, and discover the richness of the diversity that they and others carry through multilingual kamishibaïs!

This portrait is part of the production of the booklet entitled “Guide for any educational structure wishing to set up a Plurilingual Kamishibaï contest” updated in the framework of the Erasmus+ Kamilala project.

To find out more about this kami-nity , please visit the page of Dulala’s contest.

To discover the winning plurilingual Kamishibaïs of the contest in France, visit our gallery.