Regional inspector of education for plurilingualism

Aosta Valley Region

Plurilingual Kamishibaï contest since 2018

Extract of an interview conducted by Delphine Leroy on February 15th, 2020 in Aosta, in the framework of the Erasmus+ Kamilala project.

The context

One day, a colleague told me, “So, Ms. Vernetto, bilingual education, is that you?” I told him that bilingual education is the Aosta Valley!

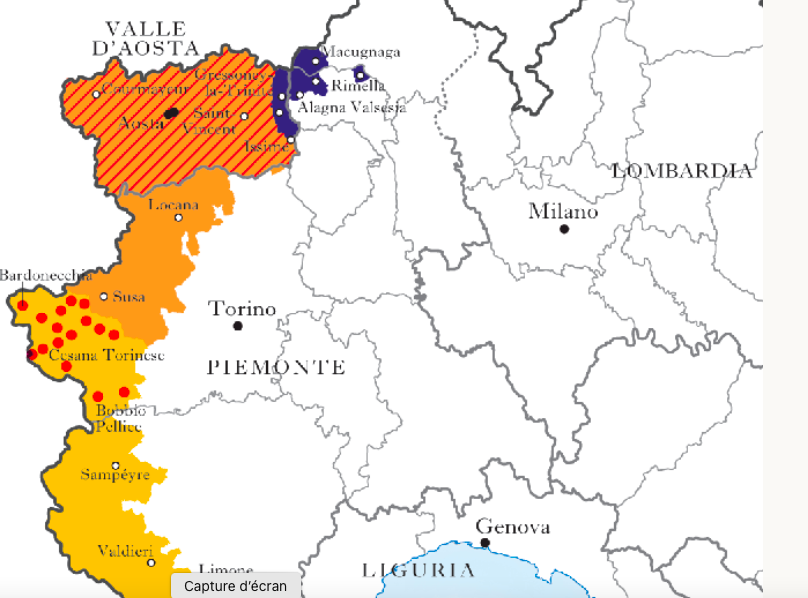

In a small territory, several languages coexist: Italian and French, the official languages, German, and particularly the variants Titsch and Töitschu, Francoprovençal and the languages of migration, past (Italian dialects) and present. It is a constant site of experimentation. For a multilingual didacticist, this is an ideal work site, because multilingualism is essentially a way of perceiving and existing in the world.

It is around the linguistic particularities of the region that a form of territorial recognition is manifested and of course, the linguistic issues have broad implications on societal life. In this context, the role of the French language, and the way it’s viewed, has an obvious political dimension for the Italian speaker whether he is Francophone or not. For example, to be able to work in the Aosta Valley, it is necessary to pass a French exam. These influences impact individual families and my task is to opt for neutrality in this debate while promoting multilingualism, an ambitious task that seems facilitated by the fact that I am not a Valdostan native.

In our school system, Italian and French coexist from kindergarten up. Children learn to read and write in Italian and French at the same time. Then, the disciplines are taught in both languages. So, sometimes, the kamishibaï or the bilingual storybook or the French storybook is used as a gateway to disciplinary content among the youngest.

In order to have an overview of the language skills that pupils attain throughout their schooling, a system of regional language tests is also in place in the Aosta Valley in addition to the national system of standardized tests for Italian, math and English. It concerns the second and fifth grade classes, the final year of middle school, then the second and senior years of high school. The languages evaluated are French for all school levels and German for classes in the Walser community. The tests follow the Common European Framework of Reference and are based on the four language activities: written and oral comprehension and production. All pupils in an age group take part in this evaluation and receive certification of the language level attained. It is a way to recognize and value their commitment to language learning.

For a frontier region, which bases its economy mainly on tourism, proficiency in several languages is important.

It is not surprising, then, that the promotion of plurilingualism characterizes our educational language policies, which naturally led us to take a pluralistic approach to languages and cultures. Our approach, especially the work with teachers, allowed us to incorporate these plural approaches in the curriculum of the Aosta Valley at all levels of education – it worked because we started from the base. We experimented alongside teachers who often tell me: “I could not do otherwise. Now that I have learned to do this, I could no longer go back, I could no longer do things differently.

We worked directly from the field because teachers often blame inspectors for their lack of praxis: “You’re in your office, you’re in your ivory tower, and also, we don’t know how to proceed.” There, however, it was the opposite.

Our region has become a research ground that attracts more and more students, researchers who intervene in our schools to study our system or to carry out the experimental phase of their work.

Bio

After high school, I studied medicine for two years. I had no desire to teach, far from it. That was the least of my worries. And then there was Mexico…

I left for family reasons and since I had free time I wanted to take German courses at the Alliance Française. Mastering a fifth language could make it easier for me to find work when I return to Europe.

When I arrived to register, the director told me that, sorry, the German teacher had to return to Europe and that she had to cancel the course. But she offers me to give Italian lessons because people ask to learn this language.

I told her I had never taught, I didn’t know how. But I tried. Why not? I had some time to fill: I started out like this and I loved it. And I began giving French courses as well.

This is how I started my career as a language teacher abroad for an adult audience in the context of mobility. Without putting words on it, I had an active and communicative approach. I was unable to teach French in the traditional way… take up the manual, explain, do the exercise.

Back in Italy, I resumed my studies at the Faculty of Languages to become a teacher and at the end of my whole course I told myself that I could not go to schools like that. I didn’t feel that I had learned to teach. So, I went through training, first in France and then in Spain.

The first year of teaching I was assigned to a linguistic high school. I offered my students global simulations, or I asked them to invent comic strips. I thought they were excellent, they had a good level of French both orally and in writing. In October (the schools start in September) I enter the teachers’ room where a colleague approaches me, because we both had the first-year classes. She said, “Oh, they’re at a terrible level.” I responded that I don’t feel that way. “We did an assignment and guess what? They did not know the feminine form of ‘boar'”. I looked at her and said, “Listen, I’ve never met a boar in my life. If I ever met one, the last thing I would worry about is whether its female or not.” She did grammar checks, vocabulary checks: boars, sows, young boars, stuff like that. But what interest does this represent in the learning of the language, its functioning, the lexicon? And then the students hated it because it was only memorization that finally had no meaning.

After a few years I became an instructor and started teaching at the university. Courses in French first, then language didactics and children’s literature for future teachers.

There again I studied: I went to see how the francophones were using the children’s books and I started to train my students and teachers in this way, experimenting with them. I could not envision university teaching for this audience solely as a theoretical teaching.

I’ve always tried to figure out how to show what can be done based on theory. And this is my chance: I am always in between, I rely a bit more on the practical aspect of the tools, but always with a well-defined theoretical anchor. That’s my “housekeeping” side. You have to be concrete.

Some students tell me: Before starting this course, I told myself that I would never teach languages, that it is too difficult. I can’t do it. Now I know I can do it. It’s still difficult. I realize that, but at least I have theoretical points of reference and, above all, I know how to do it. And I know how to solve problems if I encounter them.”

I suggest to my students a chef’s pose. I tell them: “You can do Bofrost pedagogy (which is a company that delivers frozen food at home), that is to say you open the fridge, you look at what frozen foods you have there. You microwave them, and you put everyone at the table. But I want you to do a Masterchef pedagogy: that is to say that you have guests, each guest has his needs, has his different style. One is allergic to leeks, another hates meat. You open the fridge and you decide with what you have in the fridge, what you can do for this audience.”

The contest

The organization of the plurilingual Kamishibaï Competitions is a long story that began in 2009. We embarked on the experimentation of language awareness and, more generally, plural approaches in Valle d’Aosta, notably thanks to a European project (Coménius Regio) realized with bilingual French/Occitan and French/Catalan schools of the Academy of Montpellier. It was a project around a tool, the story bags, that we carried out in collaboration with Michel Candellier, who provided training for our teachers, and Elisabeth Zurbriggen, who was in charge of the process in Geneva. Story bags are used in different French-speaking countries: Canada, Luxembourg, France. The particularity of our approach is that we have also involved regional languages: Francoprovençal and Titsch for the Aosta Valley, Occitan and Catalan for the Montpellier academy. The results were conclusive, the project was of great richness and its dissemination spread rapidly. Here too, our asset has been to concretely demonstrate to teachers the benefits of language learning from a support designed for them and adapted to our context.

Indeed, the advantage of a European project is that it makes it possible to have the funds to experiment, to do research and training, that is to say to associate research with teacher training and experiment to see if the system works. This was the case with the story bags. Initially, I could not know if this tool would work, if the teachers were ready to appropriate it. But because of the European project, an experimental protocol was deployed, follow-up questionnaires for teachers, pupils and parents were administered, a scientific committee coordinated and accompanied all the activities and validated the productions. Once the outcome was approved, it was time to disseminate and expand the training to more teachers. And we could rely on solid experience and data.

Many of our teachers then entered the system. From there, as the Occitan colleagues used kamishibaï in a bilingual way (French/Occitan or French/Catalan), they trained our teachers in this technique, and we set about a first kamishibaï project.

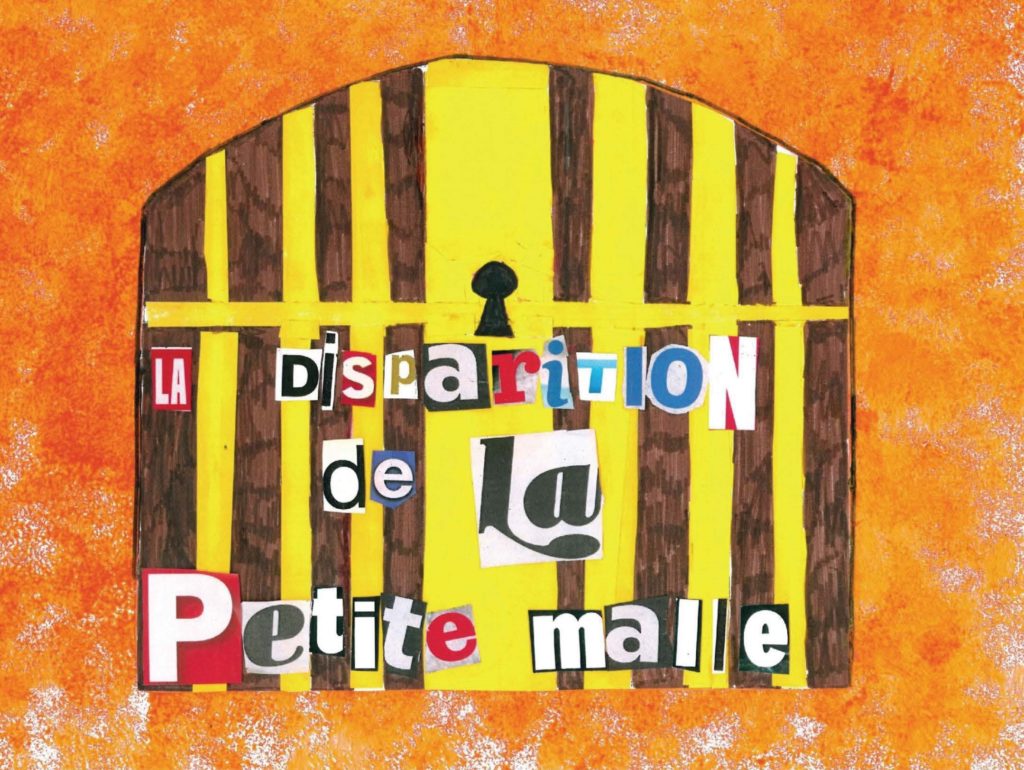

Thanks to Dulala, I was invited to the international competition in 2017. The idea of creating initial national or regional competitions, to subsequently participate in the supranational competition was launched. In 2018 the first edition of the Plurilingual Kamishibaï Contest took place, and we have continued ever since.

I don’t think it’s cumbersome to organize it, I have a team working with me. And then, what motivated me was really the enthusiasm of the teachers. Last year (2018), we had a thousand and some students who participated in the contest. And this year too, we started the kamishibaï in kindergarten, elementary school. Now we have middle school classes that are participating as well.

Teachers’ need to share their experience and to confront each other is also fulfilled by sharing around the organization of the contest. I wanted to put them in touch so that they could communicate about new things, preventing them from getting tired. That is to say, to encourage them to always work on plural approaches, language awareness, all the while having the impression of doing something different.

Portrait conducted within the framework of the booklet entitled “Guide for any educational structure wishing to develop a Kamishibaï contest,” updated in the framework of the Erasmus+ Kamilala project.